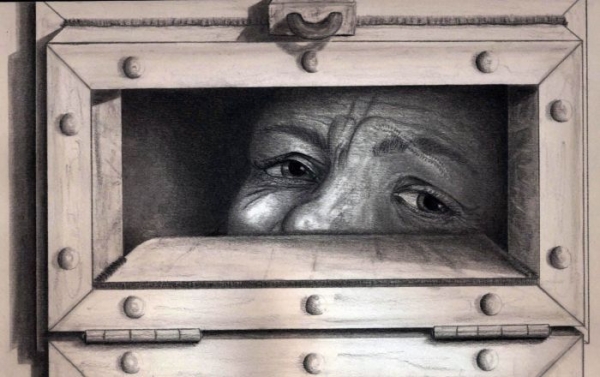

The case against Indiana’s Department of Correction centered on three inmates with mental illnesses who were placed in solitary confinement — or, per the state’s preferred euphemism, “restricted status housing” — which meant almost no out-of-cell time, limited contact with other inmates and prison staff, and punishments that exacerbate or give rise to mental problems. Except in a few, exceptional circumstances, prisoners with various types of mental illness will no longer have to endure the barbarity of solitary. Crucially, this is a broadly defined group, including not only people who are schizophrenic or bipolar but also those who suffer from anxiety disorders and other mental maladies that can lead to self-harm or functional impairment.

Mental-health experts will have much more leeway in determining the conditions in which their patients must live. The goal is to get them out of solitary and into an environment that might help — or at least not hinder — their treatment. To that end, the settlement requires that mentally ill inmates receive at least 10 hours of therapeutic out-of-cell time per week, a dramatic shift in current practice, and frequent in-cell visits from clinicians. These prisoners will also get more unstructured, recreational time outside their cells. The American Civil Liberties Union’s Amy Fettig says that these changes, particularly the out-of-cell requirements, match what many other states have done — either by choice or in response to a lawsuit — and are emerging as de facto national standards.

Even so, declining to torture the mentally ill is a low bar. Other states have done much more. Colorado, for example, scaled back its old solitary confinement system, significantly reducing the number of people the state isolates. The state’s head of prisons reports that disorder has not resulted. Instead, Colorado has shown that corrections officers have any number of more humane ways to keep order.

Protecting particularly vulnerable inmates is important, but so is reducing the use of solitary as a general, routine punishment for minor rule-breaking. Also essential is providing step-down programs that prepare those who have been isolated for life in the general prison population — or in larger society after their terms are up.

Every state may have a few inmates who are too dangerous to house with other people. But that is no excuse to continue the rank, rampant overuse of solitary confinement.

Link to original article from The Washington Post

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'

ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'  "These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein

"These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein  How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.

How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.  What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on

What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto

On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in

A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen

In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed

Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed