- Home

- About

- Campaigns

- PDA Radio

- Contact Us

- Downloads

- Join Us

- Donate

- Events

- Benefit Kitchen

McAuliffe restores rights of more than 5,100 ex-offenders

James W. Ray sat silently in the front row of the church meeting room, rubbing his eyes. Ray wasn’t mourning a loss. Rather, the Vietnam veteran and felon wept over something that had just been returned to him — the right to vote.

How Much of a Difference Did New Voting Restrictions Make in Yesterday's Close Races?

The Republican electoral sweep in yesterday’s elections has put an end to speculation over whether new laws making it harder to vote in 21 states would help determine control of the Senate this year. But while we can breathe a sigh of relief that the electoral outcomes won’t be mired in litigation, a quick look at the numbers shows that in several key races, the margin of victory came very close to the likely margin of disenfranchisement.

Where Did All the Black Voters Go on Election Day?

With midterm hangover setting in, many will chatter and finger-point into next month about what happened, who did what and why. And at the center of it will be questions about the black vote. In crucial Senate and gubernatorial races where the black vote was needed most—Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, North Carolina—Democrats faced humiliating blows to the stomach.

Young people's voice needed in building an infrastructure of opportunity

This week the Durham, North Carolina-based nonprofit MDC released its latest State of the South report highlighting how the American dream of intergenerational upward mobility is more elusive for young people born at the bottom of the income ladder in the South than anywhere else in the country.

Some Fauquier Citizens Trapped in "Medicaid Gap"

A group of his constituents met last week with Del. Michael J. Webert (R-18th/Marshall) to tell him how lack of adequate health care affects them and to enlist his support for a solution. From all ages and walks of life, they met Thursday, Aug. 7, at the cooperative extension service office in Warrenton.

The Last Gasp Of Jim Crow: The High-Stakes Battle To Restore Voting Rights To 350,000 Virginians

Mercedies Harris strolls down the halls of the Hollaback and Restore Project, a felon rehabilitation center in rural Virginia, and points to a baby-faced 18-year-old with a timid gait. “This is a fine young gentleman who got into a little trouble,” he explains. “And we are working with him to try to stop him from being a statistic and being incarcerated and having a record. He’s going to learn to be a barista. And if he gets good, he’ll be known for it,” he chuckles. “People will be coming here to get his coffee.”

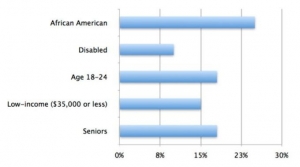

200,000 in Va. may lack proper ID needed to vote

About 200,000 voters in Virginia may lack the proper identification needed to cast a ballot in the November midterm elections, state election officials said Thursday.

Under a state law that took effect this year, Virginia voters must present a driver’s license or some other form of photo identification at their polling stations before they cast a vote.